Male Golden-winged Warbler. Photo by Zack Grasso.

In May 2015, DGIF sponsored an intrepid crew from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) to set off for Bath and Highland counties to outfit small migratory songbirds with tiny data loggers, also known as geolocators, to track the birds’ movements over the period of a year. The birds are Golden-winged Warblers, a rapidly declining species which breeds in the shrubby, high-elevation valleys of western Virginia and which winters in Latin America. The work was part of a broader effort across 14 states and Canadian provinces to describe the migratory routes and wintering ground locations of two golden-wing populations, one of which breeds in the Appalachians (and includes the Virginia birds) and the other in the Great Lakes region. The Appalachian population has been particularly hard-hit, declining to a mere 5% of its original size since the 1960s, while the Great Lakes population is relatively stable.

Geolocator units used to track Golden-winged Warbler movements.

In May 2016, again with funding from DGIF, VCU returned to their study sites to retrieve as many of the geolocator units as possible. This involved finding returning golden-wings, recapturing the birds, removing the units and releasing the birds again; VCU was successful in retrieving 5 units from birds in Highland County. Unfortunately, due to defects in the geolocators, only 2 of the 5 had usable data; similarly, only 48 of 76 units recovered across the broader study area had collected roughly a year’s worth of data.

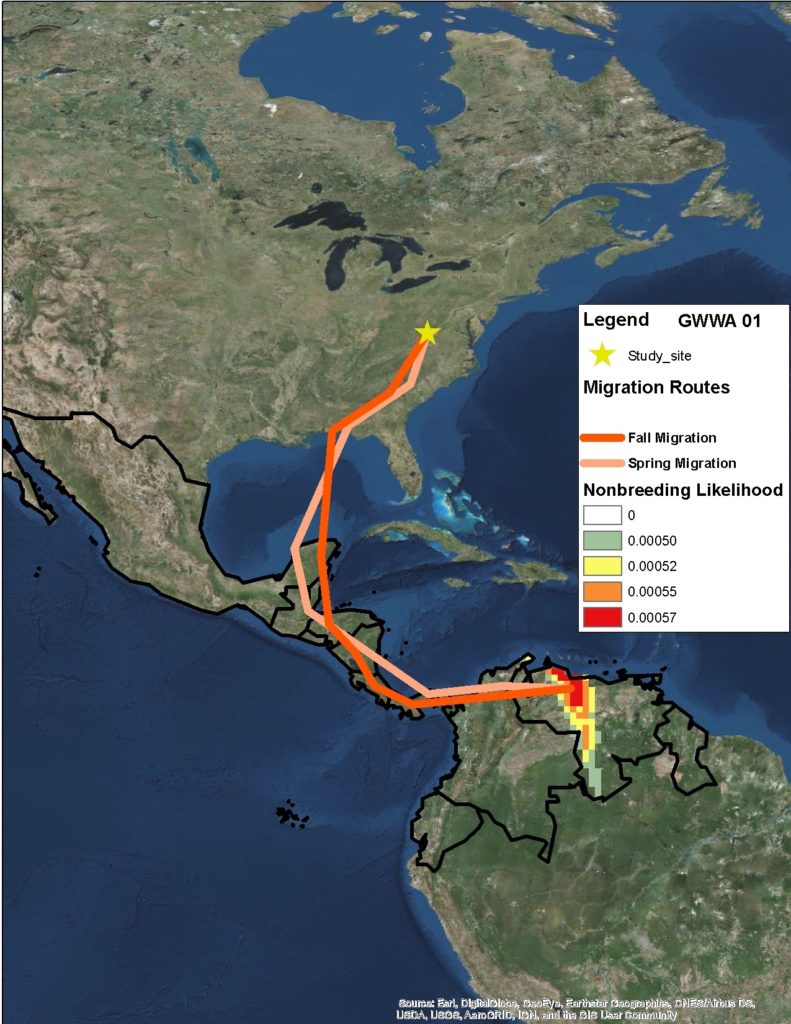

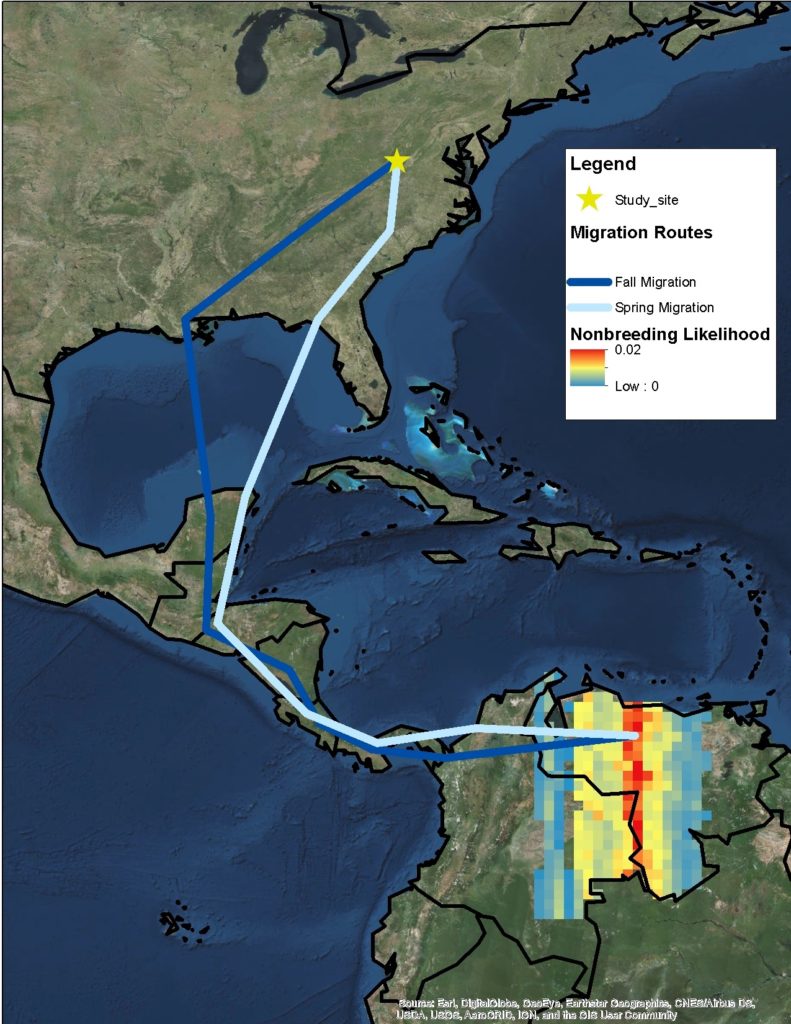

Despite this setback, the data harvested from the geolocators proved to be very valuable. It showed that in 2015, the two golden-wings each made a roughly 3,200 mile journey from Highland County to their wintering grounds in north-central Venezuela. This included travel through the southeastern US, across the Gulf of Mexico, and through Central America to reach their wintering destination in northern South America! Leaving their wintering grounds in March of 2016, they then roughly followed the same route in reverse to return to within 500 feet of their 2015 breeding sites.

- Likely spring and fall migration routes and wintering location of Golden-winged Warbler captured in Highland County, based on geolocator data. Red color indicates the most-likely wintering area. Map by Gunnar Kramer.

- Likely spring and fall migration routes and wintering location of Golden-winged Warbler captured in Highland County, based on geolocator data. Red color indicates the most-likely wintering area. Map by Gunnar Kramer.

The results from the broader study are even more telling: golden-wings from declining populations in other Appalachian states, like the Virginia birds, had also wintered in northern South America; while birds from the stable Great Lakes population largely spent the winter months in Central America. In addition, the closely-related and relatively stable Blue-winged Warbler, which breeds in both the Appalachian and Great Lakes regions, wintered almost exclusively in Central America. The birds with the declining populations are consistently spending the winter in northern South America, whereas the birds with relatively stable populations are wintering in Central America. This evidence strongly suggests that events that take place away from their breeding grounds are driving the declines of the Appalachian golden-wing population. For example, the loss and fragmentation of forested landscapes were disproportionately greater in northern South America than in Central America between the early-1940s and 1980; this roughly corresponds to the period of greatest decline of the Appalachian golden-wing population. In addition, Appalachian golden-wings travel farther distances during migration than do the Great Lakes warblers; obstacles to successful migration may therefore be greater for the Appalachian birds.

Searching for Golden-winged Warblers in Highland County. Photo by Jessie Reese.

Despite these findings that point to wintering grounds habitat loss as a limiting factor, maintaining an ample supply of golden-wing habitat on the breeding grounds remains a priority. Without the proper management, the shrublands on which the species depends will revert to forest. However, the results of this study force us to take a critical look at how the North American bird conservation community allocates its efforts. While we have traditionally focused on the breeding grounds here in the U.S., it may be important to step up our work with Latin American partners south of our borders. Such efforts will be crucial for the long-term survival of declining long-distance migrant birds, which pay no heed to political boundaries.

How to help the Golden-winged Warbler

- Help document the breeding status and distribution of golden-wings and many other bird species in the Commonwealth by participating in Virginia’s Second Breeding Bird Atlas, now in its third of 5 years.

- Consider donating to DGIF’s Non-Game Fund so that we can continue funding projects, such as this, that contribute to cutting edge research on Virginia’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need.