The largest of the anadromous herring (or “clupeids”) in Virginia is the American shad, which once migrated westward in the James River to Covington and beyond. The magnitude and sheer number of fish involved in these great migrations astonished early Europeans such as Alexander Whitaker, who wrote in 1613, “The rivers abound with fish both small and great. The sea-fish come into our rivers in March… great schools of herring come in first; shads of a great bigness follow them.” As the settlers pushed westward, they continued to marvel at the abundance of fish that appeared each spring. Robert Beverley, a historian, wrote in 1705, “In the spring of the year, herrings come up in such abundance… to spawn, that it is almost impossible to ride through, without treading on them.”

What happened to the American shad (Alosa sapidissima)?

The Latin name, sapidissima, means “most delicious” or “most palatable,” but to Native Americans and early settlers, the spawning runs of shad and herring each spring meant the difference between starvation and survival after the hardships of winter. By the 18th century, American shad and river herring had become one of the leading commodities in the colonial economy, but that’s also when problems began to arise for these fish. The increased construction of dams effectively blocked the upriver migration of anadromous fish. No longer could these fish make their way to upland spawning and nursery grounds. Faced with the challenges and changes of urbanization and industrialization, populations of American shad steadily declined over time. In 1994, a moratorium on the inland harvest of shad brought an end to the rich and deep traditions that both the commercial watermen and recreational anglers had enjoyed for centuries.

A Rocky Road to Recovery

In an effort to reintroduce and enhance American Shad in the James River (while planning on-going fish passage structures at the Richmond dams), the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries began a restoration program in 1992 which continued through spring 2017. This project used state and federal hatcheries to reintroduce “tagged” shad fry into the upper James River system. A similar restoration effort on the Rappahannock River started in 2003 and ran through 2014. Hatchery reared fry raised from springtime Pamunkey River (and later from the Potomac River) brood stock were stocked in the James River upstream of Richmond. Egg taking operations on the Potomac River, in the vicinity of Fort Belvoir, provided hatchery fry used to stock the Rappahannock and James Rivers. The Potomac collections were performed through a partnership with the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. As mitigation for egg collections, the Pamunkey and Potomac rivers also receive annual fry stockings. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Harrison Lake Fish Hatchery was a crucial partner in hatchery rearing and stocking of fry throughout the course of this project, as was the VMRC until it ceased funding for the project after 2008 due to budgetary constraints.

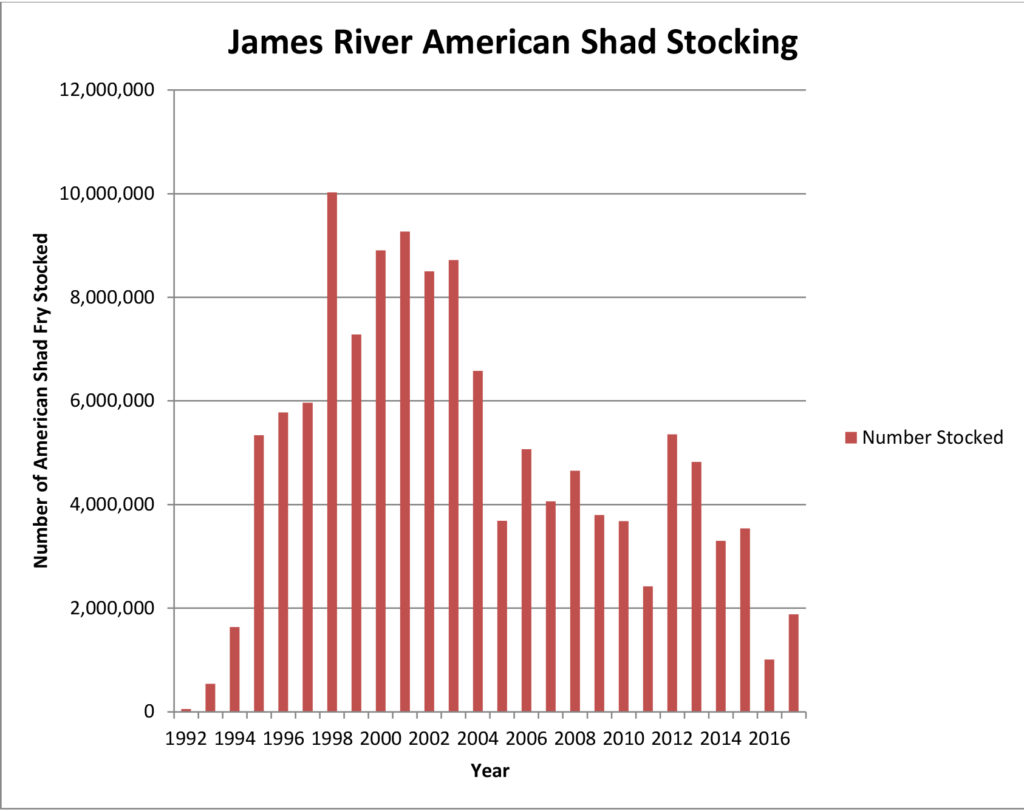

While initial targets for stocking were 10 million fry annually to the James River above Bosher’s Dam, after loss of funding from VMRC the target number of stocked fry was scaled back to 4 million annually in the period after 2008. Even with a reduced target, VDGIF and its partners in restoration have been unable to meet even this reduced target in recent years. This was largely due to declines of returning adult shad in the Pamunkey River (the primary source of brood fish), In fact, given logistical constraints and limited numbers of available brood fish, since its inception the program has rarely been able to its target goals for stocking (Figure 1).

Sadly, off-shore fisheries have been theorized to impact American Shad populations to the point of limiting recovery potential, and therefore negating restoration efforts by state agencies and their restoration partners; efforts focused on fish passage to increase access to historic spawning habitat and/or stocking to supplement spawning stocks. Other factors have been identified as potential roadblocks to recovery as well (e.g.; dams and other blockages and other habitat alterations). With the likely bottlenecks to recovery occurring in areas outside of VDGIF’s jurisdiction and given a lack of expected response (reestablishment of American Shad runs to the James above Bosher’s and recovery of the James River American Shad population) in spite of decades-long stocking efforts, VDGIF will not be stocking American Shad in the foreseeable future. Having limited funds for resource management, VDGIF has determined that funds are better utilized in program areas with likely efficacy. VDGIF is stepping back from its American Shad stocking program until such time as offshore bycatch impacts can be adequately evaluated, and the Virginia Alosine Taskforce (composed of scientists, biologists, fishery managers, tribes, and other interested parties with expertise in American Shad) recommends stocking as a viable and necessary management strategy for restoration.

Figure 1 – Numbers of American Shad fry stocked into the James River from 1992 through 2017.

Recent and total fry stockings are given in the following table:

| Year | River | Number of Fry Stocked |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | James | 1,879,628 |

| Rappahannock | 0 | |

| Total Per River System (since 1992) |

James | 125,846,446 |

| Pamunkey | 28,255,646 | |

| Potomac | 6,203,420 | |

| Rappahannock | 50,219,422 | |

| Grand Total | 193,502,188 | |

How did we get there?

By March 15 of each year, biologists from the Department and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are busy monitoring water temperatures in Virginia’s tidal rivers as hatchery crews busily prepare themselves to receive the first shad eggs of the season. As water temperatures rise into the low to mid 50s, shad actively begin to spawn, creating a flurry of activity by all those involved in the project. Lengthening days and warming water temperatures find biologists and commercial fishermen hard at work collecting brood stock shad for egg-taking operations. Using floating gill nets, the watermen lay out a webbed wall that moves with the tide. The nets move through a section of river (“driving the reach”) a short time before the tide reaches the ebb, or slack, tide, to collect spawning fish. Generally, tides only run over a 4-hour period, giving the egg-taking crews small windows of opportunity. Shad spawn primarily from late evening until midnight, requiring most of the work to be done at night.

Most male shad collected each evening are ready to spawn, but not all females. Those that are not, are released back into the river. Females in spawning condition and releasing eggs freely (“flowing”) are quickly removed from the nets by the watermen and placed on boats with live wells. The broodstock are then taken to shore where the egg-taking process is done. Flowing fish are manually spawned into bowls by massaging the fish’s belly. Water is then added to the bowls, which activates the sperm and fertilizes the eggs. Egg fertilization rates can be improved from 5-35% in the wild to as much as 95% through this manual spawning effort.

Once fertilized, the eggs are placed in water-filled tubs and left undisturbed for a one-hour period. During that time, the eggs will absorb water and swell to twice their original size — a process known as becoming “water hardened.” During this time, biologists are also collecting information about the adult fish to find out more about the age and growth of American shad spawning in the state.

Once water-hardened, the eggs are then placed in oxygen-filled bags and taken to the hatchery. There, the eggs are counted before being placed into hatching jars to incubate until hatched. The young shad, or fry, hatch in 6 to 8 days, depending on water temperatures. The jars are then placed into 200-gallon circular tanks where the fry will remain for the next 3 to 7 days. During their stay at the hatchery, the fry are fed a combination of brine shrimp and salmon starter feed and marked with a permanent tag. Tagging hatchery-raised fish is necessary to distinguish them from wild fish, allowing biologists to evaluate the success of their restoration efforts. After 3 to 7 days, the fry are loaded back into trucks and are stocked into the James and Rappahannock rivers and their tributaries.

State and federal wildlife agencies often use hatchery operations in recovery efforts of suppressed fish populations. Such efforts are not intended to sustain a troubled fishery, but are designed to give recovery efforts a head start. The road to recovery for Virginia’s American shad populations will be a long and difficult one. The cooperation, dedication, and hard work between all of the partners, including the commercial watermen, is testimony to the importance and sense of urgency that is needed for recovery efforts of this magnificent and most beneficial fish.