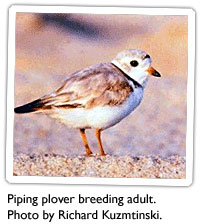

Considered to be a true master of camouflage, the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) is a small, inconspicuous shorebird with a sand-colored back, narrow black neck ring, white belly, orange legs and a small orange and black bill. Even its bell-like call is indiscreet and endearing. In 1986, the US/Canada Atlantic Coast piping plover breeding population was listed as federally threatened under provisions of the US Endangered Species Act. Virginia is part of this population’s southern breeding range and since 1986 has supported a relatively stable number of nesting pairs (Figure 1). Piping plovers typically nest on sparsely vegetated ocean-facing beaches, sand flats and washovers. Since the late 1990’s, 100% of the breeding activity in Virginia has occurred on the Eastern Shore’s barrier islands. Many of the barrier islands provide ideal breeding habitat in the form of wide beaches with extensive wash-over areas that offer unimpeded access to mudflats, sandflats, tidal shorelines and other feeding areas where insects, marine worms, and other terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates are abundant and within easy reach of hungry plovers.

Considered to be a true master of camouflage, the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) is a small, inconspicuous shorebird with a sand-colored back, narrow black neck ring, white belly, orange legs and a small orange and black bill. Even its bell-like call is indiscreet and endearing. In 1986, the US/Canada Atlantic Coast piping plover breeding population was listed as federally threatened under provisions of the US Endangered Species Act. Virginia is part of this population’s southern breeding range and since 1986 has supported a relatively stable number of nesting pairs (Figure 1). Piping plovers typically nest on sparsely vegetated ocean-facing beaches, sand flats and washovers. Since the late 1990’s, 100% of the breeding activity in Virginia has occurred on the Eastern Shore’s barrier islands. Many of the barrier islands provide ideal breeding habitat in the form of wide beaches with extensive wash-over areas that offer unimpeded access to mudflats, sandflats, tidal shorelines and other feeding areas where insects, marine worms, and other terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates are abundant and within easy reach of hungry plovers.

Every spring, piping plovers return to their breeding grounds and upon their arrival, the males attempt to attract mates by performing a series of complex aerial and ground displays. They also have the added task of staking out a breeding territory and defending it against other males. Soon after a pair bond is established between a male and a receptive female, the female usually lays four eggs in a shallow scrape made in the sand. Both adults share incubation duties, which last about 25-28 days. Although chicks leave the nest within hours after hatching and immediately begin feeding on their own, their parents watch over them until they are fully-grown and able to fly. Chicks seek refuge and warmth under the adults during inclement weather, and when a potential predator enters the breeding territory one of the parents will usually perform a broken wing display to lure it away from the brood. The young are capable of sustained flight and considered to be full grown or fledged at about 25-28 days of age. Soon after the brood has fledged, the birds disperse to their southern wintering grounds. Plovers typically begin breeding at one year of age and rear only one brood per year.

In 2008, an estimated 208 piping plover pairs nested on Virginia’s barrier islands, which is the highest annual total recorded in the state since the species was federally listed (Figure 1). 2006 marked the first year the number of Piping Plover breeding pairs rose above 200, which represents a virtual doubling of the population over a three year period. Productivity studies conducted on nine of the barrier islands in 2008 collectively revealed the lowest fledging success reported in the Commonwealth since 1997 (i.e., less than one fledged chick per pair; see Table 1 and Figure 2). Tidal flooding events, depredation and increased competition for foraging habitat were some of the factors that may have contributed to this year’s low productivity.

Piping plovers have many natural enemies such as raccoons, foxes, crows, gulls and other birds and mammals who love to feast on eggs, chicks and an occasional adult bird. Storms and spring high tides often wash out a portion of the nests and/or drown flightless chicks. Humans visiting the barrier islands during the breeding season may unknowingly take their toll on plovers as well. Fortunately, people can do a lot to minimize disturbance to nesting birds. Listed below are a few simple measures to take when visiting the barrier islands during the breeding season (April – September):

- Keep pets at home since they are not allowed on most islands. Unleashed dogs will often flush incubating adults from their nests or chase after young birds.

- Always remain as close to the water’s edge as possible. Avoid wandering over dry beach or vegetated areas (i.e., dune grass, marsh grass, and scrub/shrub habitats) where birds might nest and stay away from mudflats where young chicks and adults actively feed.

- Keep out of all posted nesting areas and stay at least 100 yards from any nesting bird or bird colony. People venturing near nesting sites may cause adult birds to leave the nest thereby exposing unattended eggs or chicks to predators or excessive temperatures. People may also inadvertently step on well-camouflaged eggs or chicks.

- Always pay attention to the birds around you. The birds will let you know if you are too close by vocalizing, taking flight, and/or exhibiting defensive behaviors.

- Avoid disruptive activities such as camping, campfires, fireworks, kite-flying and loud parties. These activities are generally not allowed on any of the islands.

- Take all trash with you when you leave the islands.

Note that many of the barrier islands are closed to the public either year round or during the breeding season. If you have questions regarding island closures or wish to learn more about piping plovers please call The Nature Conservancy at (757) 442-3049, the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Natural Heritage Program at (757) 787-5576, Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge at (757) 336-6122, Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge at (757) 331-2760, or the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries at (757) 787-5911.

Figure 1. Annual number of Piping Plover breeding pairs (end-of-season totals) in Virginia, 1986 – 2008.

Figure 2. Annual statewide Piping Plover productivity estimates in Virginia, 1990 – 2008. Annual estimates obtained from 75% of nests laid each year.

Table 1. Piping Plover productivity estimates on Virginia’s barrier islands. The number of pairs monitored for productivity (n = 202) represents 97% of Virginia’s end-of-season Piping Plover breeding population (n = 208 pairs).

| Site | # of Pairs Monitored | # of Chicks Fledged | 2008 Productivity Estimates (2007) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Islands | |||

| Assateague Island1 | 46 | 27 | 0.59 (1.08) |

| Assawoman Island1 | 26 | 30 | 1.15 (1.74) |

| Metompkin Island | 60 | 59 | 0.98 (1.47) |

| Cedar Island | 38 | 31 | 0.82 (0.63) |

| N. Island Totals | 170 | 147 | 0.86 ( 1.21) |

| Southern Islands | |||

| Wreck Island | 3 | 1 | 0.33 (1.00) |

| Ship Shoal Island | 9 | 8 | 0.89 (0.45) |

| Myrtle Island | 6 | 6 | 1.00 (1.00) |

| Smith Island | 10 | 12 | 1.20 (1.86) |

| Fisherman Island2 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 (0.00) |

| S. Island Totals | 32 | 28 | 0.88 (0.91) |

| Statewide Estimate | 202 | 175 | 0.87 (1.16) |

- 1 Data provided by Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge.

- 2 Data provided by Eastern Shore of Virginia National Wildlife Refuge.