Male golden-winged warbler. Observed in Tazewell County, Virginia. Photo by Baron Lin.

Male golden-winged warbler. Photo by Tom Benson.

Female golden-winged warbler. Photo by Alan M., Flickr Creative Commons

Fact File

Scientific Name: Vermivora chrysoptera

Classification: Bird, Order Passeriformes, Family Parulidae

Relatives: wood warblers

Conservation Status:

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need-Tier 1a on the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan

- Petitioned for listing as a threatened species in the U.S. under the Endangered Species Act (since 2012)

- Listed on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List

- Listed as Threatened under the Species at Risk Act in Canada

Size: about 5 inches long

Life Span: 7 years and 11 months maximum, but overall this has been poorly recorded

Habitat: associated with varied types of open shrublands near forests. In Virginia, they occur at high elevations, generally over 2000 ft., primarily in old fields and lightly grazed pastures near forest edges. May also use regenerating clear-cuts, young forests, powerline right-of-ways, and shrubby wetlands that are close to forest. Shrubs in the Rubus genus (especially blackberry) are often found in breeding habitat.

Diet: moths, caterpillars (especially leafroller caterpillars), as well as other insects and spiders

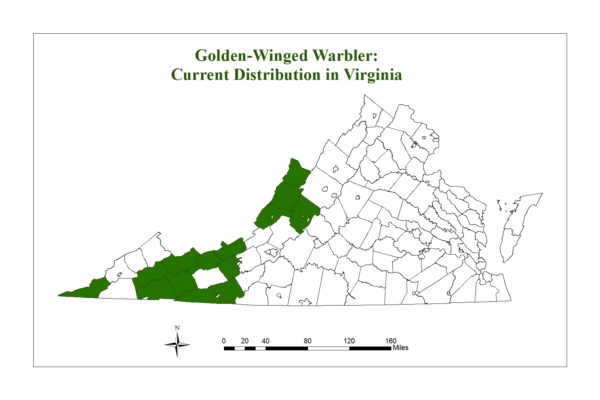

Distribution: Long-distance migrant. Breeds throughout the Great Lakes Region of the US and Canada and scattered in localized sites of the Appalachian Mountains. They winter in southern Central America and northern South America, including Guatemala, Honduras southward to Venezuela and Colombia. In Virginia, due to their high elevation requirements, they are restricted to areas west of the Blue Ridge with their highest abundances in Highland County and areas of southwest Virginia.

Identifying Characteristics

Male golden-winged warbler. Photo by Melanie Underwood.

Males: A vibrant yellow cap on top of the head and matching brilliant yellow wing patch are the most distinctive markings on this attractive songbird. Other striking facial markings include large black patches across the eyes and throat, which are highlighted with a streak of white across the “eyebrow” and a streak of white down the malar/ “mustache.” They have a light grey back and a dingy white underside, sometimes with a subtle buffy yellow wash on the nape of the neck, back, or underside.

Female golden-winged warbler. Photo by Andrew Cannizzaro.

Females: Female golden-winged warblers appear overall similar to the males, but they are generally duller with less striking markings.

Watch Your Step!

Golden-wings have the distinction of being just one of a few warbler species that nests on or near the ground. The female will often build the nest at the base of a blackberry or goldenrod stalk, using the stem for support.

Golden-winged warbler at its nest with nestlings. Photo by California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Birds of a Feather: Golden-winged and Blue-winged Warblers

Blue-winged warbler. Photo by Tom Murray.

Golden-wings are very closely related to the blue-winged warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera) – a 2016 Cornell study estimates that the two species share 99.97% of their genetic material. The two warblers will readily breed with one another, producing two hybrid types known as Brewster’s warbler and Lawrence’s warbler. (Hybrids are offspring resulting from the breeding of related but otherwise distinct species.)

These two hybrid warblers have intermediate plumage characteristics between their two parent species. Additional plumage variations can be seen in offspring occurring from one of these hybrid birds mating with a “pure” blue- or golden-winged warbler. Confounding identification even further, birds that aesthetically appear to be “pure” golden-winged or “pure” blue-winged warbler based on their plumage may actually share genetic material with the other species – it is estimated that ~8% of Virginia golden-wings may in fact be ‘”cryptic hybrids.” Although hybridization is not uncommon in birds, it appears to play an outsized role for the golden-winged warbler.

- Brewster’s warbler. Photo by Steven Kersting.

- Lawrence’s warbler. Photo by Dominic Sherony.

Role in the Web of Life

In conjunction with other insect-eating birds, the golden-winged warbler’s diet of insects and other arthropods helps keep these populations in check.

Golden-winged warblers are affected by brown-headed cowbirds, a bird that is considered a nest parasite due to its behavior of laying eggs in the nest of other bird species, leaving its young to be cared for by other parents. In the case of golden-winged warblers, adults may abandon their nest if it is found to contain a brown-headed cowbird.

- Golden-winged warbler nest containing a cowbird egg (the larger of the five eggs), observed in Smyth County, Virginia. Photo by Baron Lin.

- Golden-winged warbler nest, containing golden-winged warbler nestlings (top and right) and a cowbird nestling (left), observed in Smyth County, Virginia. Photo by Baron Lin.

Where to See in Virginia

In Virginia, golden-winged warblers can be challenging to find due to their dwindling populations and the fact that most of their habitat is located on privately owned lands. For a chance at finding the bird, visit the sites listed below where golden-winged warblers have been documented. All these sites are either open to the public or offer some degree of public access.

Male golden-winged warbler, observed in Highland County. Photo by Alison Sloop.

Tips: As a long distance migrant, the golden-winged warbler arrives to Virginia in May and departs in August/September. The most reliable area to find golden-wings during the breeding season (May – July) is in the high-elevation valleys of Highland County. During spring and fall migration, it may be possible to spot a golden-wing in some of the other listed areas. When seeking golden-winged warblers at any of these sites, focus your attention on open areas where there are patchy/ scattered shrubs and trees and a ground cover of grasses and blackberries.

Best-bet Sites (breeding season)

Highland County: Blue Grass Valley Driving Loop and along other low traffic rural roads in the county’s high elevation valleys

Bath County: Hidden Valley Campground, George Washington National Forest

Tazewell County: Burke’s Garden

Smyth County: Appalachian Trail (AT) along the Tilson Tract of George Washington & Jefferson National Forest – located in Ceres, VA off Rt. 610/ Old Rich Valley Rd., where the AT crosses Rt. 610 – look for the AT trail crossing sign; there is a pull-off there for parking – contact info: Mt. Rogers National Recreation Area: 276-783-5196, Brittany.phillips@usda.gov

Wythe County: Crawfish Valley and the Appalachian Trail, near the Settler’s Museum of Southwest Virginia

Other Sites to Try (migration seasons)

Rockingham County: Switzer Lake Area and Hillandale Park

Albemarle County: Ivy Creek Natural Area

Botetourt County: Warbler Road and Claytor Nature Study Center of Lynchburg College

Conservation

The Road to Recovery

According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, the golden-winged warbler has lost an estimated two-thirds of its population since 1970, making its decline amongst the steepest of any North American songbird. The majority of these declines have occurred in the Appalachian population, which includes Virginia: with declines of close to 9% per year, it is losing ground at a rate that is nearly 10 times that of the Great Lakes population. Reasons for golden-wing declines may include habitat loss on the North American breeding grounds and the Latin American wintering grounds, as well as hybridization and competition with the closely-related blue-winged warbler.

Golden-winged warbler habitat at Highland WMA.

Habitat loss on the breeding grounds is largely attributed to loss of shrublands. This ephemeral habitat type can only be maintained through active land management or natural disturbance in the form of storms or wildfires. Without these events, shrublands eventually revert to forest and no longer support golden-winged warblers. However, conservation of the golden-wing warbler is not as simple as addressing habitat loss within the birds’ breeding range. Given that the warbler is a long-distance migrant that spends only one third of the year on its breeding grounds, it’s possible that the species’ decline may also be due to factors occurring where it winters and along its migration routes. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about habitat loss on the wintering grounds, where golden-wings use forests at elevations of 3,600 to 6,600 ft.

An additional challenge to golden-winged warbler conservation is its prevalent hybridization, as the species may run the risk of being genetically swamped out by the more common blue-winged warbler. Furthermore, blue-winged warblers may be outcompeting golden-wings in areas where both occur. How one manages for golden-wings while excluding blue-wings, which can be found in the same habitats, is still an open question.

In the face of these various threats to golden-winged warbler populations, conservationists are rising to the challenge through collaborative and partner-based approaches. Formed in 2003, the international Golden-winged Warbler Working Group is a partnership of state and federal agencies, universities and non-profit organizations. The Group has developed a Conservation Plan for the golden-winged warbler that provides guidance for the creation and maintenance of habitat on the bird’s breeding grounds as well as a plan for its non-breeding season/ winter range. In addition, the federal Working Lands for Wildlife program provides financial assistance to private landowners willing to engage in management practices that will benefit golden-wings.

What the DWR Has Done/Is Doing

VCU banding a male golden-winged warbler in Highland County as part of a DWR funded-research study. Photo by Dan Albrecht-Mallinger.

The DWR, which leads the Virginia Golden-winged Warbler Partners Group, has been working to address the declining warbler population in Virginia through multiple strategies, including surveys, monitoring, research studies, outreach to private landowners, and restoring golden-winged warbler habitat on the agency’s properties.

Research

Since 2006, the DWR has worked with partners to learn more about the status and conservation needs of the golden-winged warbler in Virginia. We have conducted and funded surveys, with partners such as Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), to determine the species’ distribution within Virginia and its population numbers. These data are helping prioritize locations for conservation efforts. The DWR also annually coordinates the monitoring of golden-wings in Virginia as part of a broader effort, led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, to track their population trajectory.

VCU field technician retrieving a geolocator unit from a golden-winged warbler as part of a DWR-funded research study. Geolocators were outfitted on the birds to track their migration routes. The geolocators were then removed the following year to retrieve the data. Photo by Jessie Reese.

In addition to the surveys and monitoring, the DWR has funded and collaborated with VCU on a number of research projects that will assist in developing conservation strategies for the species. Results from these projects have deepened our understanding of the species’ habitat needs in Virginia, informed whether we can attract golden-wings to new breeding areas by broadcasting their song, and identified sites where golden-winged warblers winter. Through the latter study, we learned that birds breeding in the Appalachians, including Virginia, wintered in northern South America (Colombia/Venezuela), while those nesting in the Great Lakes region wintered in Central America. These results suggest that the disproportionate decline of golden-wings in the Appalachians may be partially tied to habitat loss in South America. The implication is that conservation work in the United States alone may not be enough to reverse golden-wing population declines. DWR and partners have already begun follow-up by sponsoring surveys for the species on its South American wintering grounds.

Outreach to Landowners

Because the majority of shrublands in Virginia are in private ownership and active management is required to maintain them, outreach to landowners is critical to ensuring a good supply of golden-winged warbler habitat. In 2018, the DWR, in collaboration with VCU, took initial steps towards such outreach by conducting a survey of private landowners in southwest Virginia. Understanding landowner attitudes toward shrubland habitat management and wildlife, as well as challenges to implementing management, is critical toward tailoring a message that is most helpful to landowners.

Habitat Restoration

Habitat restoration site at Highland WMA.

In addition to working with private landowners, the DWR is working to expand breeding opportunities for golden-winged warbler on our Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) through a pilot project on Highland WMA. In late 2017, we began improving habitat in four existing forest openings along the ridgeline of Jack Mountain within the WMA in order to increase available habitat for golden-winged warblers. These improvements include connecting two existing openings by removing trees in between them, thus creating a larger, core area of open golden-wing habitat; facilitating shrub growth through natural seed dispersal; and cutting back forest edges to create shrubby conditions. Ultimately, this project seeks to expand habitat for an existing population of golden-winged warblers breeding in the adjacent valley, so that they may colonize new areas and grow in number. In the meantime, these shrubland habitat improvements are also helping a large number of other bird species, including field sparrows, Eastern towhees, brown thrashers and warblers such as chestnut-sided warbler and yellow-breasted chat.

Learn More About Our Work

- Prospecting for Gold – The Golden-Winged Warbler on Highland WMA (2022)

- Warblers on Working Lands: Restoring Shrublands for Wildlife (2019)

- Tracking the Golden Winged Warbler from the Highlands of Virginia to South America (2018)

- Tracking the Golden Winged Warbler (2016)

How You Can Help

- Purchase a Restore the Wild Membership to support the DWR’s habitat restoration work, such as that in progress for golden-winged warblers at Highland WMA. The membership also serves as your pass to visit this WMA and over 40 others throughout the Commonwealth.

- Donate to DWR’s Non-game Fund to support research and conservation of Virginia’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need, like the golden-winged warbler, as well as conservation education and wildlife viewing recreation.

- If you are a landowner west of the Blue Ridge, learn how you can improve habitat on your property for golden-winged warbler. Contact your local DWR Private Lands Wildlife Biologist for a consultation or refer to this helpful guide for land managers and landowners.

- Start e-Birding. Submit all of your golden-winged warbler observations to eBird. This public database is utilized by ornithologists and conservationists. Your observations may help inform their work!

- Keep cats indoors and restrain when outdoors. Golden-winged warblers are ground nesters, making them extra vulnerable to free roaming cats.

- Stay on designated trails, while enjoying the outdoors. Golden-winged warblers often nest on the ground along edges of roads and trails, making them vulnerable to wandering footsteps, horse hooves, bike tires, and off-road vehicles.

Sources

Species Profile Authors: Sergio Harding, DWR Non-game Bird Conservation Biologist, and Jessica Ruthenberg, DWR Watchable Wildlife Biologist

Last updated: August 3, 2022